In Memoriam: Anne-Marie Hutchinson OBE, QC (Hon)

Chair's Tribute

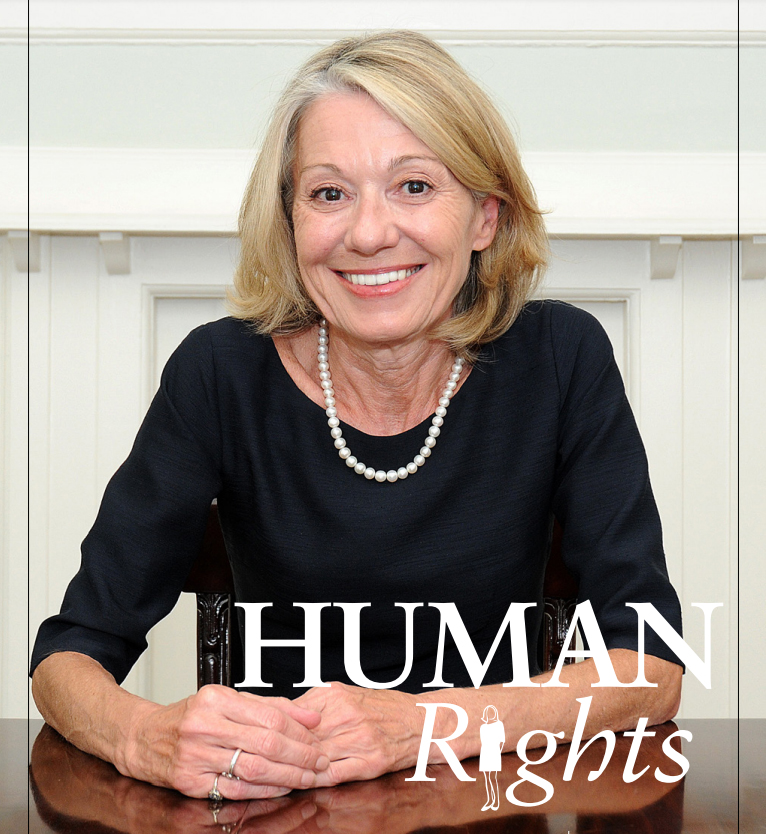

Anne-Marie Hutchinson was an exceptional person.

She was an excellent lawyer and a most valued partner in the law firm Dawson Cornwell where she headed the family law department. She had a broad experience of family law but may be best remembered for her expertise in international family law. One speciality was child abduction. That is where I met her many times at family law conferences at The Hague and in the UK.

Another speciality was her work for and support of victims/survivors of forced marriage. When my Vice-chair, Nasreen Rehman, and I set up the Forced Marriage Commission which I chair, Anne-Marie was an obvious choice as a commissioner. Her help was invaluable; she made an important contribution to the legal section of the draft report and advised us as we prepared our final consultations.

Anne-Marie chaired many important committees and was widely recognised for her outstanding contribution to family law, culminating in the award of the OBE in 2016.

She will also be remembered by all who knew her for her kindness and generosity and her wisdom and judgment.

She was a pillar of our Commission and a good friend to so many of us. She will be widely missed.”

Elizabeth Butler-Sloss

Chair

The National Commission on Forced Marriage UK

Anne-Marie's Funeral was held on 30/10/20

Reunite's Tribute

Posted on 5 October 2020 | by reunite

It is with great sadness and heavy hearts that we announce the loss of Anne-Marie Hutchinson OBE, QC (Hon) on 2nd October 2020 after a long illness.

Anne-Marie was our Chair of Trustees for almost three decades, during which time she steered reunite through considerable change and championed our aims and our vision with a ferocity and strength that was immeasurable.

Anne-Marie was known across the world for her groundbreaking work in the field of child abduction and was recognised as the leading lawyer of her generation. There are many professionals who have been touched by, informed and inspired into action by her.

Over the years she has acted for the victims of child abduction, forced marriages, abandoned spouses, honour based violence and female genital mutilation. She has done so much for those who are most vulnerable and who, without her efforts, would have remained victims.

Anne-Marie embodied our organisation and we honour her. We will miss her ‘can do’ attitude, her acerbic humour, her love of life, her sense of fun, her generosity towards others and her boundless energy. She leaves an incredible legacy, much of it visible in our continuing work. We will take reunite forward in her name and spirit.

Anne-Marie was also a proud mother and grandmother and our sympathies and love go to her children, Catherine and Sam, and her granddaughter Emmeline.

Anne-Marie's Obituary in the Guardian

Posted on 19 October 2020 | by Caroline Baksi, The Guardian

Family lawyer who did pioneering work on forced marriage and child abduction

Anne-Marie Hutchinson, who has died aged 63 of cancer, was a trailblazing family lawyer, renowned for her groundbreaking work on forced marriage and international child abduction. A partner at the London law firm Dawson Cornwell, she also acted for victims of “honour”-based violence and female genital mutilation, abandoned spouses, and potential parents in surrogacy arrangements. Innovative and involved in the most reported cases of any solicitor in her field, she often sought to extend principles of English law and the court’s jurisdiction, to afford rights and protection to those she represented.

In 1999, in the first reported English case on forced marriage, she secured the safe return to England of a young Sikh girl who was made a ward of court after her parents abducted her to India to marry. A case in which she represented an English-born Pakistani woman set a legal precedent in 2006 when the high court ruled for the first time that a forced marriage could be annulled, due to the lack of consent, and declared void.

Her work was instrumental in the introduction the following year of the Forced Marriage (Civil Protection) Act 2007, which enabled courts to make orders to prevent women and girls being taken overseas to marry against their will.

The year after the act was introduced, Anne-Marie acted for Humayra Abedin, a trainee GP, who was the first woman to be made the subject of such an order. She had been taken to Bangladesh, where she was held captive and forced to marry. Even though the injunction made by the English court against Abedin’s family was not enforceable in Bangladesh, the judge in Dhaka acknowledged its existence when he ordered her to be released.

In another landmark case in 2012, the high court ordered the return to the UK of Amina Al-Jeffrey, a British woman with dual Saudi Arabian nationality. Born in Wales, she alleged that she had been taken to Jeddah against her will and held in what she described as a cage for four years by her father, who disapproved of her life in the UK.

While some viewed much of her work in the context of a clash of cultures, for Anne-Marie it was about respect for human rights, which were afforded to everyone equally – whether she was acting for a woman forced to marry or potential parents looking to create a family through surrogacy.

A proud member of England’s Irish Catholic diaspora, Anne-Marie was born in Donegal, the third of six children. Her mother, Kitty (nee Fitzgerald), was a nurse and her father, Gerry Hutchinson, ran a barber’s shop. When she was a child, the family moved to the UK where her father got a job on a US airbase near Huntingdon, Cambridgeshire.

Osteomyelitis – bone infection – forced her to miss the last two years of primary school and she spent a year in Addenbrooke’s hospital in Cambridge, after which she had to wear a calliper and learn to walk again. Having failed the 11-plus, she left St Peter’s school, Huntingdon, at 16 with only basic qualifications. For two years she worked as a bank teller before enrolling in Huntingdon technical college – leaving a year later with three A-levels at grade A.

A degree in international history and politics at Leeds University was followed by a law degree at Nottingham University, before she qualified as a solicitor at the north London law firm Beckman & Beckman in 1985. There her mentor, Jack Bleiman, convinced her to change her focus from commercial and civil litigation, and she quickly developed a reputation acting in child abduction cases in the early days of the Hague convention, a treaty that provided a mechanism for the return of internationally abducted children.

The high-octane work involved her dragging judges out of the bath in the early hours to secure a return order, going air side at Heathrow to lift a snatched child off a plane, and heading to Col Muammar Gaddafi’s Libya armed only with an high court order, and its Arabic translation, to rescue a snatched baby. Her daughter Catherine, who also works at Dawson Cornwell, recalled: “It would not be unusual to have clients and children stay at our house after they had just been rescued at Heathrow.”

Anne-Marie travelled the world, speaking at conferences and seminars, sharing her knowledge and helping to cultivate and inspire the next generation of international family lawyers.

She was a commissioner on the Forced Marriage Commission set up in 2013. Its chair, the former court of appeal judge Lady (Elizabeth) Butler-Sloss, described Anne-Marie as an “exceptional person” whose premature death will “leave a great gap in a very important and not always well-understood branch of law”.

Anne-Marie was made an OBE in 2002 and an honorary QC in 2016, and received an honorary doctorate of laws from the University of Leeds.

Passionate and fuelled by adrenaline and a diet of caffeine, nicotine and cava, Anne-Marie was known for her sense of fun, glamorous style and large collection of footwear and handbags, but she could also be “seriously terrifying”, said her colleague Carolina Pedreño, adding: “You don’t achieve as she did without a touch of steel.” Away from work, Anne-Marie enjoyed reading, particularly spy novels, and was a great cook, whose roast dinners were accompanied by the biggest Yorkshire puddings.

Anne-Marie is survived by her daughter, Catherine, son, Sam, and granddaughter, Emmeline, as well as her siblings, Geraldine, Paul and Catherine.

• Anne-Marie Hutchinson, lawyer, born 1 August 1957; died 2 October 2020Anne-Marie's alumni profile

AS WELL AS SHAPING GOVERNMENT POLICY, ANNE-MARIE HUTCHINSON SAVES VICTIMS OF CHILD ABDUCTION AND FORCED MARRIAGE. NOT BAD FOR A STUDENT WITH NO FIXED CAREER PLAN, SHE TELLS CHRISSIE RUSSELL

There are nights when all Anne-Marie Hutchinson OBE QC (Hon) can do is sit with her mobile phone in the dark, hoping that a text will come through to tell her that a client is safe and well. Many of the top human rights lawyer’s cases are life and death: children wrenched from their mothers’ arms, young girls forcibly wed to men they don’t know, let alone love, and innocent people trapped in countries they long to leave, denied their basic freedoms.

Anne-Marie (International History and Politics 1980, Hon LLD 2016) has fearlessly assisted in the protection of more than 150 forced marriage victims. She was recently named one of the Top 50 Women Super Lawyers and was honoured with an Outstanding International Woman Lawyer Award. This summer the University awarded her an Honorary Doctor of Laws.

And yet – reassuringly for many students – Anne-Marie had no idea what she wanted to be when she grew up. Born in Donegal, but brought up in Cambridgeshire from the age of two, she was one of six children. There was no tradition of the Law in her house. Her mum was a nurse and her dad, a hairdresser.

She failed the 11 plus and went to a secondary modern school, then left at 16 before returning to education at a technical college. She headed to Leeds “because it was the hardest place to get into,” with an unexpected three grade As at A level.

On graduating, Anne-Marie thought law might interest her as a career, so she did a conversion course and entered the field of civil law in 1985. Her first case wasn’t a headline-making international human rights case, but a landlord and tenant dispute.

She didn’t have a rigid career plan. “It was all very organic for me and I think that’s how it should be,” Anne-Marie reveals. “I often get sent requests and CVs saying ‘I want to do human rights’ or ‘I want to do women’s rights’ or ‘I want to do forced marriage.’ I always write back to them and say ‘well, that’s actually quite insular and probably not the best way to start your career’. It’s much better to take all the opportunities you get to have the broadest spectrum of education and experience.”

It was a mixture of fluke, being in the right place at the right time and interest that led to her portfolio of cases associated with women’s and children’s rights. Anne-Marie joined the family law firm Dawson Cornwell in 1998, was awarded the first UNICEF Child Rights Lawyer Award in 1999 and later given an OBE for battling international child abduction and adoption. In 2004 she was named Legal Aid Lawyer of the Year for work with victims of forced marriage.

The work can be all-consuming. “There are some cases where you are motivated by a passion largely because of the feeling – on my side, anyway – that otherwise a huge injustice would be done,” she explains, “particularly when you realise there are huge communities of women who are not able to access their rights and living in cultures that deter them from doing so. They can be separated from their children and would not even think to pursue an application to have custody of them.

“That’s just wrong. That’s just morally wrong and unjust.”

But not every case ends in success. “There are cases that I haven’t managed to achieve, girls I haven’t managed to get back, girls who’ve said to me, ‘I’m not strong enough to go through with this. I’m going to stay where I am’ and I know they’ve been got at… Those make me sad. Those are hard.”

Anne-Marie cites in particular the case of an Asian girl, pregnant by a European boy. The girl’s parents persuaded her to go to India to have the baby and promised she could return home with the child. “Having got their daughter into India, they tried to organise a termination,” says Anne-Marie. “That wasn’t happening because it was so late in the pregnancy. But then the baby was born and it disappeared. We spent about two years trying to find that child and we never have.”

As a mum of two herself, surely it must be impossible not to be burdened by such loss and cruelty? “It’s no different than being a doctor,” she says frankly. “That’s what I can do, I’m trained to do it. You have to distance yourself, otherwise you’re not a very good lawyer. If you can’t keep that professional distance, your judgement goes.”

She gets a huge sense of reward from working on policy and trying to establish cohesive political momentum behind it, “so the next person that comes along doesn’t feel so isolated”.

Just this May, Anne-Marie was appointed to an independent review into the application of Sharia Law in England and Wales. She feels one major challenge is confronting stereotypes in the wider community, where people say “Oh, that’s what ‘they’ do”. Another issue is to challenge thinking where young people – women in particular – are raised to believe that their path in life can only go one way.

When she first started working with women in forced marriages Anne-Marie faced hostility. “Not from the young people,” she explains, “but certainly from some of the communities who’d say ‘well, who is she to be telling us? What does she know? She doesn’t understand’.”

There was also greater sexism, when occasionally she’d turn up to court to be asked where her boss was. She thinks more should still be done to help working mothers in the law profession. In her own largely female team, staff can work from home or go part-time when they become parents.

“It’s really important for firms to support women, or men, with family commitments,” she explains. “There’s no point putting all the investment in at the early end and having this gap in the middle, so their careers stall.

“There needs to be flexibility so that if women want to keep working, they can. I don’t care if they work nine to five, or at night when the kids are in bed. As long as the work gets done it makes no difference to me.” Her own working days often end at 10pm.

Outside of work, to her son and daughter, now 21 and 28, AnneMarie jokes that she’s “just mum” or “her moaning”. Filial pride did shine through in January when she was appointed Honorary Queen’s Council for the major contribution she’s made to the law of England and Wales outside of practice in the courts.

Of all the accolades, that’s the one she’s most proud of. But what she treasures more than awards are those many cards from grateful clients. “I got a card recently from a girl who I took from a forced marriage, who now works for the UN,” she reveals.

She recently visited a mother and son in Japan whom she reunited when the boy was five. “I met them, after 15 years at his graduation,” says Anne-Marie. “The mum still had the photo of me and her outside the High Court.

“The texts from girls under their code names at Christmas, the pictures sent to me on Facebook and the texts at New Year from clients saying they’re sitting with their kids and they haven’t forgotten me… just knowing I’ve helped someone do something with their lives, that means more to me than any accolade.”